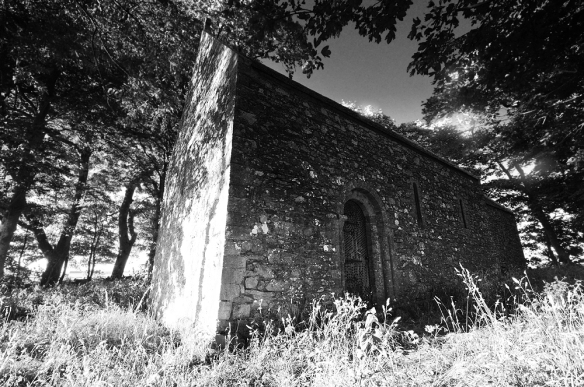

This odd church, surrounded by a high wall, hidden by trees and isolated in the middle of a field between Whithorn and Garlieston, is something of a mystery. There are tantalising glimpses however that it may have played a small part in the Scottish Wars of Independence. Could this enigmatic little church be the site of a mass grave?

This odd church, surrounded by a high wall, hidden by trees and isolated in the middle of a field between Whithorn and Garlieston, is something of a mystery. There are tantalising glimpses however that it may have played a small part in the Scottish Wars of Independence. Could this enigmatic little church be the site of a mass grave?

Little appears to be known of the church’s origins. It is supposed to have been built by Fergus of Galloway in the 12th century as a private chapel for nearby Cruggleton Castle, perched on the cliff top over-looking Wigtown Bay, also known as the Black Rock of Cree.

Although no signs have yet been found, it is possible that the church may once have been surrounded by a village. The church was granted to Whithorn Priory in 1424 and was ruinous by 1890, when it was restored by the Marquess of Bute.

There is something strangely out of character about the place when compared with other old kirks in the area, in that you quickly become aware that the burial ground contains none of the gravestones that surround other churches. There is an odd rectilinear enclosure towards the rear of the church and a line of boulders between the gate and the front of the building. Neither of these features carry any indication to what they might be.

There is however a slight clue in the folktale ‘The Standard of Denmark’, which tells of a raid on Cruggleton Castle, then inhabited by the Kerlies (an ancient Irish family that settled in Wigtownshire also known a M’Kerlie and MacCarole) by the Graemes. Eppie Graeme had fallen in love with the chief’s son Allan. The chief refused consent for them to marry, so Eppie and her father Dugald storm the castle to carry him away. The raid goes badly wrong as the Kerlies are prepared for them and both are killed along with 200 others, “on searching among the slain, they found Dugald Graeme, his head literally dashed to pieces with a stone. Upwards of two hundred were found dead, all of whom were buried in the old church-yard of Cruggleton.”*

It is known that William Kerlie lost the castle in 1282, when betrayed by his guest Lord Soulis (a secret follower of Edward I). John Comyn had temporary possession in 1292 before it was captured by Edward I. Meanwhile, William Kerlie had joined with William Wallace and retook the castle in 1297. Kerlie was still with Wallace when he was captured in 1305. Maybe the story of the mass burial in the churchyard is a mythologised memory of the inhumation of the slain from one of these battles.

It is known that William Kerlie lost the castle in 1282, when betrayed by his guest Lord Soulis (a secret follower of Edward I). John Comyn had temporary possession in 1292 before it was captured by Edward I. Meanwhile, William Kerlie had joined with William Wallace and retook the castle in 1297. Kerlie was still with Wallace when he was captured in 1305. Maybe the story of the mass burial in the churchyard is a mythologised memory of the inhumation of the slain from one of these battles.

Another explanation for the lack of gravestones could be that the parish was united with Sorbie in the 17th century. If the church fell out of use at that point, it may well be that no burials took place through the 18th and 19th centuries when the use of carved, individual grave markers where at their most fashionable.

Some have commented that Cruggleton Church has an unsettling atmosphere and it is true that when the wind rattles the branches of the trees, it gives the place a restless feeling, completely at odds with the peaceful air of other churchyards such as Kirkmaiden or Kirkmadrine. Sat alone and apart, shielded by trees, wall and high gate, Cruggleton Church does not invite visitors, offers no commanding views, no tantalising clues to its past and holds its secrets close.

*Legends of Galloway, James Denniston 1825