When I first moved to Barnsley in 2004, I was keen to discover the history of the area that I was moving to. A quick search on the brilliant megalithic.co.uk website lead me to an entry on Pastscape detailing that an Iron Age Hillfort had occupied the very hilltop on which I live in Worsbrough Common.

Although this was exciting, searches on the ground soon confirmed that nothing seemed to remain. Unlike the nearby hilltop at Stainborough, which still bears the ditches of its hillfort, Worsbrough Common has a large council estate built in the 1950s. It is likely that this swept away any traces that might have remained. The highest point of Worsbrough Common is still tantalisingly marked as ‘Castle Hill’ on OS maps. At first I thought that this might be the only trace of the hillfort that remained, but I was to find out that it came by its name for a different reason.

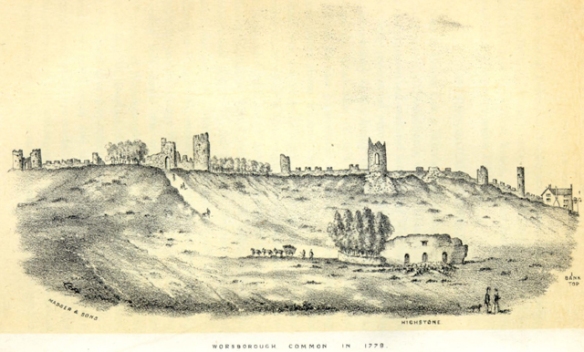

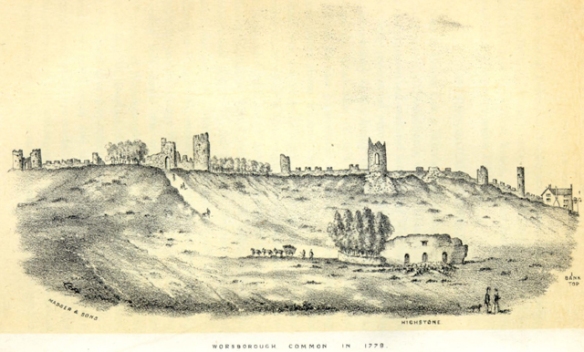

Although it seems that the hillfort is probably lost, Worsbrough has a fascinating history that has largely been preserved by the good fortune of being located on the edge of Barnsley. During my research into the hillfort, I came across an ancient tome ‘Worsbrough: Its Historical Associations and Rural Attractions’ by Joseph Wilkinson, published in 1872. Among its illustrations is an etching plate, dating from 1779 of Worsbrough Common (below) which piqued my interest.

Worsbrough Common in 1779

“The towers and trees which once stood here gave an air of antiquity and romance to the place, and the observer on contemplating from a distance their fortification-like aspect, was carried back in thought to the days of chivalry and warfare.”

Joseph Wilkinson, Worsbrough: Its Historical Associations and Rural Attractions.

The etching depicts a view across Worsbrough Common, with the Highstone (Black Rock) in the foreground and the hilltop horizon dominated by a line of castellations and towers. Although the drawing doesn’t accurately match the topography of the landscape, the drawing could have been made from memory and a certain amount of artistic license allowed, the track could correspond to the current position of Mount Vernon Road, which would place the castellations on the skyline running from Kingwell Lane, past what is now Mount Vernon Hospital, towards Black Rock and Castle Hill. As the area is now heavily built over, I considered that all trace of the castellations would now be lost. Especially as the towers have not been included on the OS map of the area, from the 1850 edition onwards, but were included on Castle Hill on the first issue OS map of the area, dated 1841.

The 1841 First Issue Ordnance Survey map of Worsbrough.

I was delighted to hear from a local source that two of the towers still survive in Kingwell Woods. In fact there is a local tale that the woods are haunted by a Blue Lady dating from the Civil War, who died by falling down and abandoned mine shaft or tunnel in the area. It didn’t take me long before I went to have a look.

Kingwell Woods is a forlorn place. A narrow strip of land on a steep bank between Elmhirst Farm and Kingwell Road, it feels like a forgotten corner of Barnsley. One of the towers is easy to find, perched high on the bank, surrounded by thick woodland, it can be seen from the road once you know where to look. It is in a sad state, perched partly on natural rock outcrops, it still has bits of walling adjoining it and the remains of stone steps leading up the steep bank. Looking like it is used as a drinking den, empty cans and the remains of a fire litter the interior.

One of the lost towers in Kingwell Wood.

The second tower is proving a bit more elusive. I headed down into the woods, but after a couple of hundred yards wading through tangles of brambles and ivy while carrying a heavy tripod, I turned back before I met the same fate as the Blue Lady. There were scatters of what could be drystone rubble, but nothing identifiable (there was a pinfold in this area that may also add to the confusion). The woods are so densely overgrown that I may have walked right past it. So that is another adventure for another day. Probably once some vegetation has died back in the winter and without heavy camera gear.

Another view of the tower in Kingwell Wood.

How did these towers come to be on a hillside in Barnsley? There was certainly no castle here throughout the medieval period and the construction is definitely not in the same fashion as medieval fortifications. The answer lies in an 18th century local family feud that came to rest on the hill on the opposite side of Dove Valley, known now as Wentworth Castle.

When the second Earl of Strafford died childless in 1695, Thomas Wentworth (1672-1739) expected to inherit the estate at Wentworth Woodhouse. However, the estate was unexpectedly passed to his cousin, Thomas Watson. In 1708, he purchased the estate of Stainborough Hall from the Cutler family and began creating an estate to rival that at Wentworth Woodhouse, changing the name to Stainborough Castle. A new Barque wing was completed in 1715 and in 1731, Thomas completed a mock castle behind the house on the hill top that was the site of the previously mentioned hillfort. He then changed the name to Wentworth Castle.

William Wentworth (1722-1791) succeeded his father in 1739 and inherited his father’s appetite for building, adding another wing to the house. The 18th century was a period with a taste for follies, usually along classical lines, they were almost always of a romantic nature. Wentworth Castle certainly has classical follies, but there was another agenda at play here.

The Wentworths were engaged in a show of one-upmanship with their relatives at Wentworth Woodhouse and what better way to promote your estate from that of a country house, than to declare it a castle of ancient origin. The estate was much larger than it is today and included the hillside of Worsbrough Common, which is clearly visible from Wentworth and a line of castellations would have looked magnificent from the grounds of the house (especially with the sun rising above them). Along with the folly on top of the hill at Stainborough Castle, it would also have given the landscape a feeling of ancient continuity.

View of Wentworth Castle from Worsbrough Common.

So what date could we attach to the building of the towers on Worsbrough Common? The 1817 Enclosure Act for Worsbrough Common gives us the following information.

“Enacted that all the Castle-ruins, and Ornamental Buildings which have formerly been erected by William Earl of Strafford, or any of his ancestors, upon the said Commons, shall, with the ground whereupon the same do stand, at all times hereafter be deemed the property of F.W.T.V. Wentworth, &c., with liberty to repair, support, and rebuild the same, and for that purpose to carry materials through and over the allotments adjoining to the said Castle-ruins, and Ornamental Buildings.”1

This seems to confirm that the towers were certainly the work of either Thomas Wentworth or his son William. If built by Thomas, they could have been constructed at the same time as the Stainborough Castle folly, around 1731. The tower in Kingwell Woods is similar in appearance to those that rise above the folly entrance.

Stainborough Castle folly, before two of the towers fell in a storm.

Another clue could be the date carved into Black Rock. It is said that the Earl of Strafford thought that the rock was hollow and intended to convert it into a summer house. This would explain the three arched doorways carved into the rock face. That date carved above the central arch is 1756, which places it firmly in the time of William Wentworth. William certainly had a taste for building follies and built the Corinthian Temple and Rotunda, which stand in the current parkland around Wentworth Castle, Archer’s Gate, Strafford Gate, Serpentine Bridge, the Obelisk at Birdwell and possibly the now lost pyramid at Blacker Hill, known as the Smoothing Iron.

The likely conclusion is that the Worsbrough Common towers were constructed at some time between 1731 and 1756. It is possible that they are contemporary with Stainborough Castle folly, but given William’s passion for folly building and that he was responsible for the masonry work on Black Rock, this could well point to him also being the builder of the Worsbrough Common towers.

It is a great shame that what remains of the towers that once dominated the Worsbrough skyline are now forgotten and in such a state of disrepair. Especially given that Wentworth Castle park has been so spectacularly restored of late. Perhaps a little bit of care and attention is over-due for this little piece of Barnsley heritage.

- Worsbrough: Its Historical Associations and Rural Attractions. Joseph Wilkinson (1872).

Centuries of habitation on what is now known as Stainborough Park, has left behind a historic landscape littered with features from a long bygone era. Nature has reclaimed much of the parkland due to neglect over the majority of the 20th century. What remains now is a valuable combination of nature and history, offering ghostly glimpses of its former grandeur.

Centuries of habitation on what is now known as Stainborough Park, has left behind a historic landscape littered with features from a long bygone era. Nature has reclaimed much of the parkland due to neglect over the majority of the 20th century. What remains now is a valuable combination of nature and history, offering ghostly glimpses of its former grandeur.

His son William inherited the estate in 1739 and carried on his father’s work – and his feud. William was responsible for not only building the Palladian wing of the house (completed in 1765), but also many of the surviving monuments and follies around the estate. I have written previously about the towers built at Worsbrough Common here.

His son William inherited the estate in 1739 and carried on his father’s work – and his feud. William was responsible for not only building the Palladian wing of the house (completed in 1765), but also many of the surviving monuments and follies around the estate. I have written previously about the towers built at Worsbrough Common here.

On a summer evening, when the warm air is full of the sound of deer fawns playing in the long grass, Stainborough Park is a magical place. If you can zone-out from the background thrum of the distant M1, it is possible to be transported to a place apart from the modern world, to a timeless haven of trees intruding on the carefully landscaped former pleasure grounds of the rich. Although in the mind’s eye, their period costumed ghosts still glide along the planted avenues and elegant gardens, their landscape has been reclaimed.

On a summer evening, when the warm air is full of the sound of deer fawns playing in the long grass, Stainborough Park is a magical place. If you can zone-out from the background thrum of the distant M1, it is possible to be transported to a place apart from the modern world, to a timeless haven of trees intruding on the carefully landscaped former pleasure grounds of the rich. Although in the mind’s eye, their period costumed ghosts still glide along the planted avenues and elegant gardens, their landscape has been reclaimed.