A small section of the Pennine Way, as it crosses Marsden Moor

This land is our land! The movement for access.

Monday 24th April 2017 will be the 85th anniversary of the infamous Kinder Trespass, an event that passed into history as an iconic, direct challenge to the age-old authority of the landowning classes. There is more to the story than just the trespass alone. It is just one incident in a long fight for access to our beautiful countryside, that has resulted in our right to roam today.

Walking high upon the hills

Rough-shod against well-heeled

A butterfly breaks upon the wheel

A compass and a cap

A sing-song and a scrap

A dotted line across the map

You Can (Mass Trespass, 1932), Chumbawamba

The Chumbawamba song ‘You Can (Mass Trespass, 1932)’ on their 2005 album ‘A Singsong and A Scrap’ captures the bravery and positive attitude of a working class movement that began at the end of the nineteenth century. The movement for access to our Pennine hills and moors by ordinary people, cooped up all week in grimy, polluted, industrialised towns and cities, in pursuit of clean air, exercise and the simple appreciation of our beautiful Pennine landscapes. A movement that eventually led to the celebrated 1932 mass trespass on Kinder Scout, the formation of our nation parks, the creation of the Pennine Way and eventually the right to roam.

Our Pennine hills have for centuries fostered the expression of free thought, radicalism and the demands for the rights of common people. Maybe it is something in the water that falls from the boundless skies, to percolate through the peat and gritstone into our reservoirs. One of the first named individuals in British history – Venutius, the estranged husband of the first century Brigantine Queen Cartimandua, made his stand against the Romans among the Pennine hills. Through the ages there are tales of King Arthur, resistance to Norman rule and Robin Hood’s exploits. The Luddites practised their drills on the moors near Huddersfield and the Chartists held their meetings on the hill tops, away from the factory owners and the prying eyes of authority. The Manchester lawyer (a contemporary of Friedrich Engels and Karl Mark) Ernest Jones’ 1846 speech to 30,000 people, among the gritstone outcrops of Blackstone Edge is still remembered.

A Chartist rally on moorland.

But waved the wind on Blackstone Height

A standard of the broad sunlight

And sung that morn with trumpet might

A sounding song of liberty!

The Blackstone Edge Gathering, Ernest Jones

At the time of the trespass, well known Peak District landscapes such as Kinder Scout (which had been enclosed in 1830), Stanage Edge and Bleaklow where the privately owned preserve of the privileged few. These grouse shooting moors were fiercely guarded by estate gamekeepers, only used for a short time each year to provide sport to the landowner and his parties of privileged friends. At Stanage Edge on most days, you will now find climbers all along the escarpments, but in the early years of the twentieth century, climbers used to bribe gamekeepers with barrels of beer to turn a blind eye, in order to pursue their sport.

It hadn’t always been this way. Even when William I parcelled up Britain into ‘Honours’ for his supporters in the Norman gentry and great swaths of our lands were declared to be Royal Hunting Parks, some common land was put aside in most manors, for use as a resource by ‘commoners’. Manorial tenants had rights to pasture their sheep, take wood and turf, fish or take sand and gravel and what was considered waste ground, was farmed by the landless.

This arrangement stood for centuries, throughout the medieval period, the English Civil War and into the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. Enclosure Acts had existed since the twelfth century, but from about the middle of the eighteenth century, the pace of enclosures of ‘common’ and ‘waste’ land increased sharply. Land would be divided into parcels (many of Yorkshire’s famous dry stone walls date from this period) and either sold or leased out. The obvious effect of this was to increase profits for the estate owners, it also saw people who had previously worked the land evicted, dispossessed and forced to move to the towns and cities to work in industry for subsistence wages. The punishment for throwing down fences that enclosed common land was death.

“For whoever may own the land, no man can own the beauty of the landscape; at all events no man can exclusively own it. Beauty is a kind of property which cannot be bought, sold or conveyed in any parchment deed, but is an inalienable common right; and he who carries the true-seeing eyes in his head, no matter how poor he may otherwise be; is the legitimate lord of the landscape.”

Walks Around Huddersfield, G. S. Phillips 1848

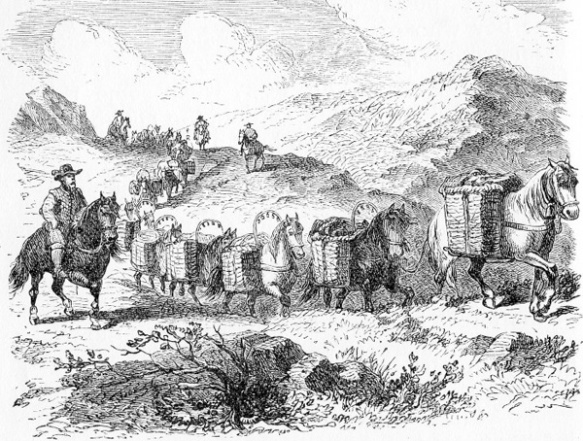

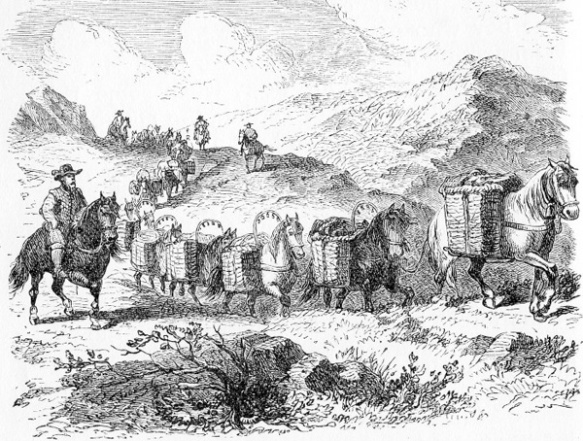

Packhorse train

As trade between the growing towns and cities increased, the informal network of tracks and hollow ways became literally bogged down and unsuitable for growing coach traffic. Turnpike Trusts were formed to build improved roads and charge a fee at toll houses to pass along them. As many of the ancient routes used for centuries had been blocked by enclosures, more traffic was forced onto the turnpikes. It is no coincidence that the landowners also tended to be trustees of the turnpike roads.

The poor man’s walk they take away,

The solace of his only day,

Where now, unseen, the flowers are blowing,

And, all unheard, the stream is flowing

Footpaths, Ebenezer Elliott

The first half of the eighteenth century was a turbulent time. The Napoleonic Wars, trade barriers, increasing mechanisation and the hated Corn Laws brought a desperate population to the brink. Probably the closest that Britain has ever come to revolution. Fearing the influence of the French Revolution would spread, the Combination Acts of 1799/1800 outlawed the formation of trade unions. This act was repealed in 1824 and a push for universal representation began, in the form of the popular movement of Chartism. By the end of the century trade unionism had entered a period of unparalleled growth and by 1918, membership stood at six and a half million, inspired by the revival of socialism.

Workers not only demanded better pay and conditions, but a better work-life balance too in the reduction of working hours to eight hours per day. It is worth remembering that at this point, the working week was still six days and workers (particularly the young) who had been cooped up in factories all week began to look for better uses of their leisure time. This led to the formation of a number of sports and recreation clubs within the growing Labour movement.

Much of the moorland of the Peak District was at this time privately owned and used for only a few days of grouse shooting per year. The latter part of the 19th century saw the moors more keenly managed for this purpose and access became even harder. The ancient footpath up William Clough on the western side of Kinder was closed by the landowner in 1877, only to be re-opened in 1897 after campaigning by the Peak District and Northern Counties Footpaths Preservation Society.

In 1900 George Herbert Bridges Ward (who became known as the ‘King of the Ramblers’, Ward’s Piece on Lose Hill is named after him), the first Secretary of the Sheffield Labour Representation Committee, formed the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers (named after the socialist newspaper ‘The Clarion’). This was the first true working class rambling club, as opposed to the existing rambling associations that tended to be composed of the middle classes, with Dukes and Earls among their patrons. Other working class rambling clubs soon followed.

Ward was convinced that the landowners were acting illegally in stopping ancient paths and bridleways across the moors and spent many long hours researching rights of way. As early as 1907 the Clarion Ramblers organised a mass trespasses on Bleaklow, again in 1911 and continued to do so until 1927, when the owner Lord Howard re-opened the Doctor’s Gate path. Regular trespasses also took place at Winnats Pass from 1926 until 1939.

The most enthusiastic enforcer of injunctions against trespassers was Manchester businessman James Watt, who owned the area around Kinder Downfall. He issued an injunction against Ward in 1923 forbidding him to trespass on Kinder Scout and from encouraging others to do the same. However, despite this Ward is pictured below, trespassing on Kinder Scout soon after in January 1924.

GHB Ward (centre with stick and white jumper) trespassing on Kinder Scout with fellow members of the Clarion Club in January, 1924. (Picture courtesy of Ann Beedham)

Only twelve legal footpaths were available to walkers, allowing access to about one percent of the Peak District, access to the vast majority of moorland was forbidden. These few footpaths became overcrowded as the number of ramblers grew. Walkers would often sneak off the paths to find quieter places, to be chased off by gamekeepers. In 1928 Ward noted that the summit of Kinder Scout was, “overrun with ramblers of all types.” It is thought that by 1932, 15,000 people left Manchester alone, every weekend to walk in the Peak District. Resentment towards the landowners was growing.

I may be a wage slave on Monday

But I am a free man on Sunday

The Manchester Rambler, Ewan MacColl

It wasn’t uncommon for ramblers to be confronted and assaulted by bands of gamekeepers, the ramblers federations received numerous complaints. The keepers didn’t always have it their own way however and Eric Byne recounted how on one occasion he and his friends were attacked by four keepers with guns and cudgels on a walk from Bradfield to Edale:

“What followed must have been a surprise. All eight of us were members of Footit’s ju-jitsu Gymnasium in Hillsborough, and after the shock of the first scuffle we succeeded in disarming the men and tossing them in the brook. This happened three times until the keepers were completely cooled down.”

The 1932 Kinder Trespass has become an iconic event in British history, a demonstration that people power can really work. Benny Rothman, one of the trespass organisers who were imprisoned for their part, became the figurehead of the trespass. He campaigned about access and environmental issues for the remainder of his life.

The initial spark for the 1932 trespass happened at the British Worker’s Sports Federation’s Easter camp (an organisation composed largely of members and supporters of the British Communist Party) that year, held at Rowarth, a few miles west of Kinder Scout. A small group headed for an organised ramble over Bleaklow. Benny Rothman recounted:

“The small band was stopped at Yellow Slacks by a group of gamekeepers. They were abused, threatened and turned back. To add to the humiliation of the Manchester ramblers, a number of those present were from the London BWSF on a visit to the Peak District, and they were astounded by the incident. There were not enough ramblers to force their way through, so, crestfallen, they had to return to camp.”

Flyers distributed around Manchester called for attendance at a rally in Hayfield Recreation Ground on 24th April. This was changed to Bowden Bridge Quarry at the last minute to avoid the police and the Parish Council, who had posted copies of local bylaws forbidding meetings there and supplied the Parish Council Clerk to read them if anyone attempted to make speeches. About 400 ramblers met at the quarry and after short speech by Benny Rothman, who stepped in when the scheduled speaker decided to pull out, set off along the legal footpath towards William Clough at 2.00pm.

The rally at Bowden Bridge Quarry.

For by Kinder, and by Bleaklow, and all through the Goyt we’ll go

We’ll ramble over mountain, moor and fen

And we’ll fight against the trespass laws for every rambler’s rights

And trespass over Kinder Scout again…

Trespass song based on a parody of ‘The Road to the Isles’.

At Nab Brow, they caught first sight of the keepers dotted along the slope beneath Sandy Heys. A whistle was sounded for the troupe to stop. On a second whistle they turned right to face Kinder Scout. When the third whistle sounded, they began to scramble up the steep slope towards the keepers. Although a few minor scuffles ensued and in some cases, the gamekeeper’s sticks were taken and turned against them, there was only one injury (a gamekeeper knocked unconscious suffered a twisted ankle). In the majority of cases, the protesters just walked through the line of keepers, they reformed at the top of the brow and were greeted by a smaller group from Sheffield who had made their way up from Edale (one account by a gamekeeper states that there was no group from Sheffield and another account says that the Sheffield group joined the rally at Ashop Head).

Low cloud skims the hill tops of William Clough, Kinder Scout.

Being unfamiliar with the terrain, the Manchester group didn’t actually make it to the summit of Kinder Scout. They instead turned towards Ashop Head where a short rally was held, before retracing their steps along the path down William Clough. They were met by the police at the Stockport Corporation Water Works and an attempt to grab someone from the crowd was chased off by the ramblers. At the beginnings of Hayfield village, they were met by an inspector in a police car, who suggested that they form a column behind him to lead them into the village. They did this and sang as they marched into Hayfield.

It was of course a trap, as when they reached the centre of the village they were stopped by police who began to search among them, accompanied by gamekeepers. Six arrests were made (five on the return to Hayfield and another later that afternoon). Benny Rothman was one of those arrested. They were first of all detained at Hayfield, then taken to New Mills, due to the crowd gathered outside calling for their release and charged with unlawful assembly and breach of the peace (notably not trespass, which was a civil offence), as the Duke of Devonshire insisted on pressing ahead with charges.

All pleaded not guilty, so Benny Rothman, Tony Gillett, Harry Mendel, Jud Clyde, John Anderson and Dave Nesbitt were committed for trial at Derby Assizes. It was said that the jury was composed of a cross section of the Derbyshire country establishment, including two brigadier generals, three colonels, two majors and two aldermen. Despite an impassioned speech by Benny Rothman, it was obvious that they were not going to get a sympathetic hearing and they were handed jail terms of between two to six months each.

The mass trespass at WInnats Pass, 1932.

The sentences, seen as draconian even then, caused outrage and probably did more to promote the cause than the trespass itself. A few weeks after the trespass, 10,000 ramblers assembled at the annual rally at Winnat’s Pass. On 18th September 1932 another trespass of about 200 Sheffield ramblers took place at Abbey Brook in the Upper Derwent Valley, via the Duke of Norfolk’s Road. The authorities had learned their lesson at Kinder Scout and did not wish for the trespass to become public knowledge, so there were no arrests this time, but upon arriving at Abbey Brook the trespassers found about forty gamekeepers and a few police waiting for them. Brief scuffles ensued before the trespassers sat down and ate their sandwiches.

The momentum for public access to the hills and moors was growing. Throughout the 1930s, moves were made towards the creation of national parks, an idea first raised by Ramsay MacDonald in 1929 and the subject of the Addison Report in 1931, although it would be another twenty years before the establishment of the Peak District National Park. The Addison Report was kicked into the long grass during the depression of the early 1930s but resurrected at a conference in 1935. The Standing Committee for National Parks was formed in 1936 and published ‘The Case for National Parks in Great Britain’ in 1938.

In 1939, the Access to Mountains Act finally passed through parliament as a Private Member’s Bill, introduced by Arthur Creech Jones (Labour MP for Shipley) but in such a mutilated form that it was described as a landowner’s charter and for the first time, made trespass a criminal offence in certain circumstances. It was bitterly opposed by the newly formed Rambler’s Association, who sought to repeal the long fought for bill.

Throughout the 1940s, the momentum towards the establishment of national parks continued, including the publication of the 1947 Hobhouse Report, suggesting 12 potential national parks. This resulted in Clement Atlee’s visionary post-war Labour Government passing the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. The Countryside Commission and the Nature Conservancy Council were formed under the new act (both merged in 2006 to form Natural England). On 17th April 1951, the Peak District National Park became the first of its kind in Britain. In 1955 the first access agreement for Kinder Scout was signed and in 1962, access to Stanage Edge was agreed.

Alongside these gradual steps towards the creation of the national parks, a special mention must be given to the remarkable Tom Stephenson who in 1935 set into motion the idea of the ‘Jubilee Trail’. Thirty long years of persistent negotiation followed, his dream eventually realised when in 1965 the Pennine Way opened, stretching roughly 268 miles from Edale to Scotland.

Imprisoned for his beliefs as a conscientious objector during the First World War, Tom Stephenson fought for access throughout his life and as Secretary of the Ramblers’ Association from 1948 to 1968, was instrumental in the creation of the national parks too.

The 1968 Countryside Act placed a duty on every minister, government department and public body to have, “due regard for conserving the natural beauty and amenity of the countryside.” In 1970, the Peak District National Park purchased the North Lees Estate, including Stanage Edge. In 1982, the National Trust bought Kinder Scout and declared it open for access in perpetuity.

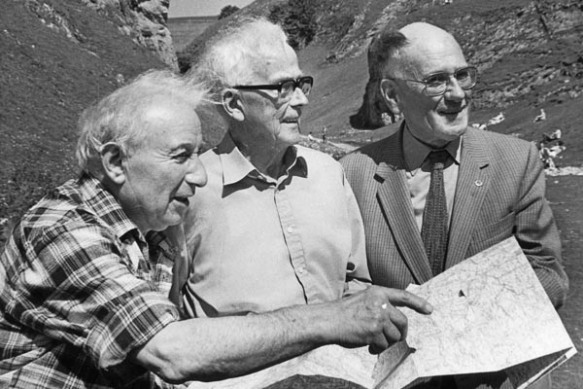

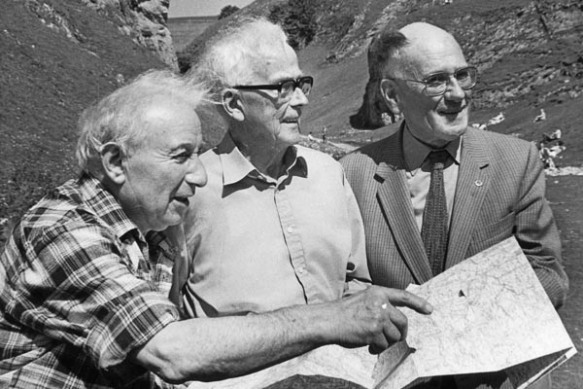

Benny Rothman (left) and Tom Stephenson (centre), Stephen Morton (right).

When the Countryside Rights of Way Act was passed in 2000, it signified the final realisation of over a century of struggle for the Right to Roam. At the 70th anniversary celebration of the trespass on Kinder in 2002, Andrew, the 11th Duke of Devonshire, publicly apologised for his grandfather’s actions:

“I am aware that I represent the villain of the piece this afternoon. But over the last 70 years times have changed and it gives me enormous pleasure to welcome walkers to my estate today. The trespass was a great shaming event on my family and the sentences handed down were appalling. But out of great evil can come great good. The trespass was the first event in the whole movement of access to the countryside and the creation of our national parks.”

Even now, in what we like to think of as an elightened age, our rights of access are under attack. The Infrastructure Act 2015 clears the way for publicly owned land to be seized and sold to private bidders with all protections such as SSSI status and rights of way extinguished. This is the same act that allows oil and gas companies to drill and frack under our homes without first seeking our permission. It could also see fracking companies invade and industrialise our National Parks, resulting in not only access to some of our best loved landscapes once again forbidden, but the potential to pollute some of our most fragile landscapes. Part of the western fringe of the Peak District National Park falls into the latest round of fracking licencing blocks and there is no guarantee that further licences won’t intrude deeper into the park in future.

When in 1990 the Peak Park Authority decided to close Kinder Scout for the whole of August, in order to discourage hunt-sabbing of the grouse shoot, public pressure soon persuaded them to change their minds. Government and fracking companies will find that they have wildly misjudged the public mood should they threaten our National Parks or countryside. Those wild Pennine hilltops are as important as any listed building and budget cuts to the Peak District National Park Authority have already threatened its continued ownership of iconic locations such as Stanage Edge. Should this act result in the sale of our public land to private interests, or a bar placed on access to our cherished landscapes, the hilltops will once again ring with demands for justice.

Benny Rothman later expressed regret that he didn’t work more closely with the ramblers’ associations of the time, who distanced themselves from the trespass and considered it to be a politically motivated attempt to grab the headlines. However, as a piece of direct action it was spectacularly successful, as it provided the public impetus that forced the issue into the open and gained a lot of public sympathy for the cause. As each anniversary slips by the trespass creates its own mythology and has come to symbolise the struggle between the working and the landed classes as effectively as the Peasant’s Revolt or the Chartists.

It is important that we keep the spirit of Benny Rothman, Tom Stephenson, Bert Ward and all of those men and women who fought for our rights to protect and access our beautiful landscapes alive.

Over looking the trespass site at William Clough towards Sandy Heys (in cloud).

The next time that you walk on the moorlands of the Peak District, or any of our spectacular hilltops, remember that raggle-taggle band of ramblers, who came to Kinder Scout from the mills and factories of Manchester and Sheffield 85 years ago. Thank them and the tireless work of the ramblers’ associations that both preceded and followed them, for the fact that you can now walk freely, where you choose in these high places of beauty. And if ever any government minister, landowner or company executive attempts to take those rights away, just ask yourself, “what would Benny do?”

A short radio documentary about the trespass ‘Witness’ is available here http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02pkd8l

This article has been adapted and expanded from the original version published in 2012 for the 80th anniversary of the trespass.

This odd church, surrounded by a high wall, hidden by trees and isolated in the middle of a field between Whithorn and Garlieston, is something of a mystery. There are tantalising glimpses however that it may have played a small part in the Scottish Wars of Independence. Could this enigmatic little church be the site of a mass grave?

This odd church, surrounded by a high wall, hidden by trees and isolated in the middle of a field between Whithorn and Garlieston, is something of a mystery. There are tantalising glimpses however that it may have played a small part in the Scottish Wars of Independence. Could this enigmatic little church be the site of a mass grave? It is known that William Kerlie lost the castle in 1282, when betrayed by his guest Lord Soulis (a secret follower of Edward I). John Comyn had temporary possession in 1292 before it was captured by Edward I. Meanwhile, William Kerlie had joined with William Wallace and retook the castle in 1297. Kerlie was still with Wallace when he was captured in 1305. Maybe the story of the mass burial in the churchyard is a mythologised memory of the inhumation of the slain from one of these battles.

It is known that William Kerlie lost the castle in 1282, when betrayed by his guest Lord Soulis (a secret follower of Edward I). John Comyn had temporary possession in 1292 before it was captured by Edward I. Meanwhile, William Kerlie had joined with William Wallace and retook the castle in 1297. Kerlie was still with Wallace when he was captured in 1305. Maybe the story of the mass burial in the churchyard is a mythologised memory of the inhumation of the slain from one of these battles.